It’s easy to assume that technological progress automatically leads to higher productivity.

New tools.

Faster computers.

Smarter algorithms.

But history tells a more complicated story.

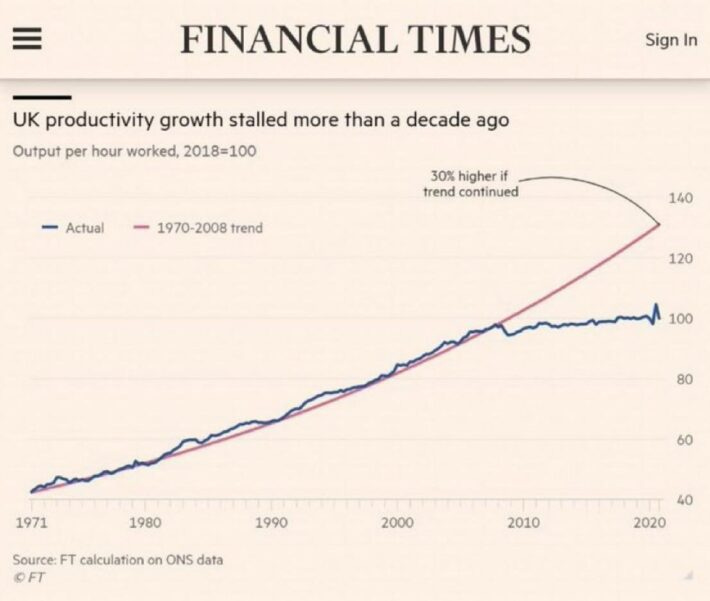

The Productivity Paradox refers to a persistent and puzzling observation: even when businesses invest heavily in cutting-edge technologies, the resulting productivity gains often fail to appear—at least right away.

This paradox became especially visible in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Companies were pouring resources into information technology.

Mainframes, personal computers, enterprise software.

Yet when economists looked at national productivity statistics, the expected surge wasn’t there.

The economy kept ticking along, but productivity growth remained sluggish.

The paradox was most famously summed up by Nobel laureate Robert Solow, who quipped in 1987:

“You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.”

It wasn’t just a clever line.

It captured a genuine mystery that has shaped decades of economic debate.

Where Did the Paradox Begin?

Let’s rewind to the 1980s and 1990s.

Businesses across industries were going digital.

But the macroeconomic data refused to reflect this transformation.

Why?

Economists and management thinkers began digging deeper.

One of the most important voices was Paul David, who, in 1990, drew a striking historical parallel.

He compared the rise of computers to the earlier electrification of factories.

Electric power arrived in the late 19th century.

But it took decades for factories to fully reorganise around it.

Simply swapping out steam engines for electric motors wasn’t enough.

Workflows had to be redesigned.

Factory layouts had to change.

Management practices had to evolve.

The lesson?

New technologies often require complementary innovations before they can unlock their full potential.

In 1993, MIT professor Erik Brynjolfsson published a seminal paper titled “The Productivity Paradox of Information Technology.”

His argument was clear.

It’s not enough to buy the tech.

You have to rethink how work gets done.

That means retraining employees.

Redesigning processes.

Building trust in the new systems.

Without these steps, technology often under-delivers—or worse, creates new inefficiencies.

Why Does the Productivity Paradox Happen?

The paradox persists for several reasons.

1. Time Lags

New tech demands organisational adaptation.

That takes time—often years.

Productivity gains don’t appear the moment you install new software or adopt new hardware.

2. Complementary Change Is Essential

Technology is just one part of the equation.

To realise its benefits, companies must also shift culture, update processes, and rethink leadership.

3. Measurement Blind Spots

Some tech creates value in ways that GDP and productivity statistics simply don’t capture.

Consider better customer experiences.

Or faster decision-making.

Or improvements in product quality.

These are real benefits—but they’re often invisible to traditional metrics.

4. Mismanagement and Misuse

New tech can backfire if deployed poorly.

Sometimes it adds complexity instead of reducing it.

In these cases, productivity can actually decline—at least temporarily.

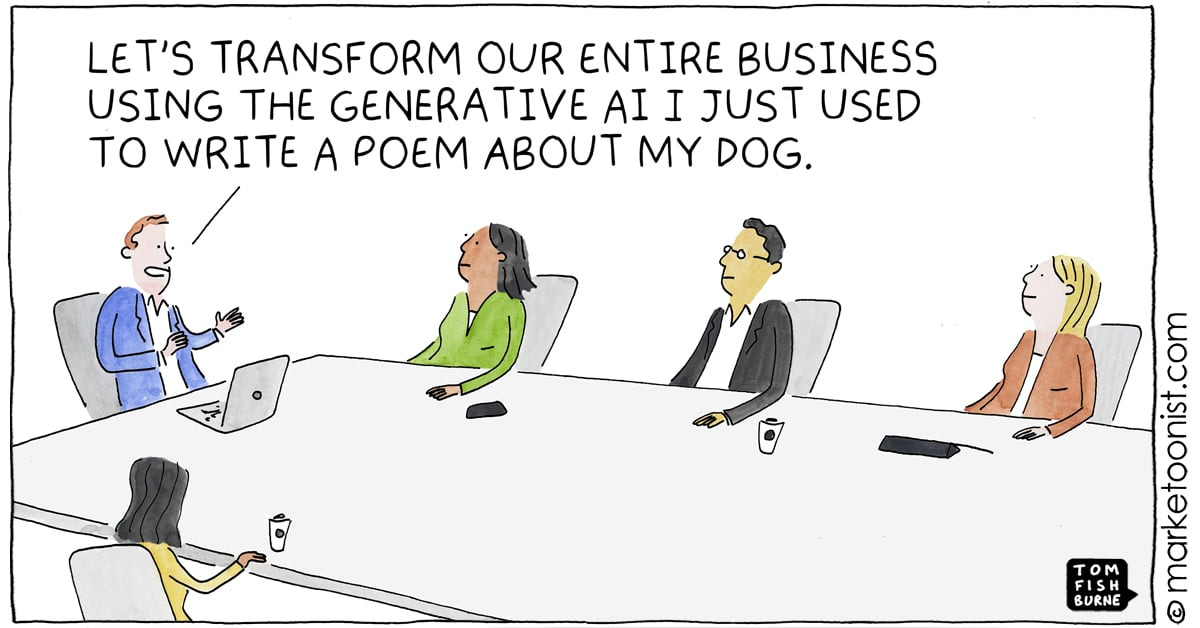

The AI Parallel: A Modern Productivity Paradox

Fast forward to today.

Artificial intelligence is following a similar trajectory.

From large language models to computer vision systems, AI capabilities are advancing at breakneck speed.

Investment is pouring in.

Startups are scaling.

Enterprises are experimenting.

Yet at the macroeconomic level, productivity growth is still lagging behind expectations.

The AI boom hasn’t (yet) translated into measurable output gains.

Why?

Four Reasons AI Is Repeating the Pattern

1. The Learning Curve

Integrating AI into real-world workflows isn’t simple.

It requires upskilling workers.

Redesigning roles.

Building trust in machine-generated outputs.

That process takes time.

2. Disruption Before Efficiency

AI is reshaping the nature of work.

But that transformation introduces short-term friction.

As companies adjust their systems, productivity often dips before it improves.

3. Invisible Value Creation

AI excels at things like personalisation, risk prediction, and creative iteration.

These improvements don’t always show up in GDP or labour productivity data.

Yet they still matter—sometimes profoundly.

4. Regulatory and Ethical Complexity

Unlike previous tech waves, AI faces significant social, legal, and ethical hurdles.

Data privacy concerns.

Bias mitigation.

Intellectual property challenges.

These frictions slow down adoption and complicate deployment.

A Final Reflection

History suggests that technology’s productivity payoff doesn’t arrive all at once.

It comes in waves.

The first wave is experimentation and learning.

The second is systems-level transformation.

Only after that does the real productivity surge begin.

AI is no different.

The leaders who understand this—those who invest in complementary change—will be the ones who reap the early rewards.

The rest will be left wondering why their shiny new tools aren’t moving the needle.